The Peck Company is a publicly traded commercial and industrial solar engineering, procurement, and construction group based in Vermont. The second generation company is focused on the northeast U.S. markets. Peck went public in the summer of 2019, and immediately the value of the stock fell. In fact, it has fallen about 80% from those initial offering amounts.

That’s rough.

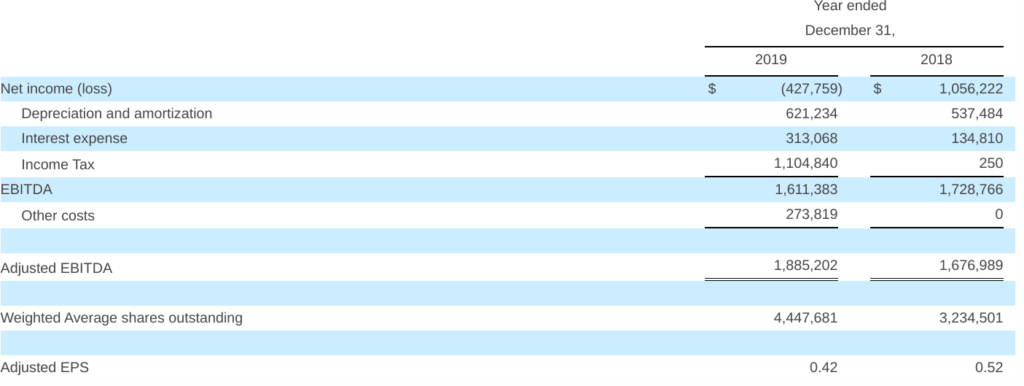

Per the company’s 2019 Q4 and full year financial results, Peck installed 35 MW across 25 projects. They earned $28.2 million in revenue for the year – up 77% on 2018, and a gross profit of $4.1 million. Their gross margins were 14.8%, down from 19.8% in 2018. And the kicker – a Net Income loss of just over $400,000 that the group suggests is due to the higher regulatory costs of going public.

Gross margins for the year ending on December 31, 2019 were lower as a result of acquiring projects directly from our development partners at the notice to proceed (NTP) phase. This strategy results in an increase in revenue and gross profit but does deteriorate the gross margin.

This lower margin logic makes absolute sense. Buying into a project at NTP means you are paying for a project that is fully papered. This means the site owner has agreed to host the solar, there is a buyer of the electricity, local zoning boards have approved the system (if a ground mount), and the electricity utility has approved the system’s connection to the power grid. Getting a project at this point in the development cycle guarantees that the construction firm is able to build the project with their team. Yes, they won’t make as high a profit margin – but they’ll make a decent chunk of cash by focusing on their specific expertise of building, instead of all of the aforementioned paperwork (which can take years to come to fruition).

Any construction company that can get into the groove of buying into projects at this point from a trusted developer relationship, will do well at generating cash flow over the long term, while limiting their project origination costs (which can involve a lot of salesperson base salaries).

Also of value is that the company is now leveraging their ability to buy projects at these developed de-risked stages, building them – and then owning them. Peck now owns 3 MW of projects. Roughly speaking, these projects might generate close to 4 million kilowatt hours/year – and if those kWhs are sold between 5-10¢ each then between $200,000-400,000 in revenue per year for decades forward are pretty much guaranteed.

Getting in this business, per Peck, generates an internal rate of return (including tax benefits), between 9% and 20%. The lower range is for projects that the company buys into at NTP, and the 20% is for projects they fully developed, over the long term, in house.

Broadly, a few key numbers look just like a standard solar construction firm. $28 million on 35 MW means about 80¢ of revenue per watt installed. This number seems a mix of projects directly sold to customers and then fully developed in-house that generate a much higher total revenue per watt installed, plus those projects the company noted it bought at NTP.

The company executed a contract to build 7 MW of projects with a development firm (work that CommercialSolarGuy also does), worth $17 million. Peck says this company has a several hundred megawatt backlog. CommercialSolarGuy happens to know a developer or two working in the northeast markets with development portfolios that size.

The firm notes a $30 million project backlog. One might assume that represents a similar megawatt volume as was deployed in 2019, as the revenue value is similar. However, it might be safer to assume the cost per watt is similar to the 7 MW/$17 million value developer deal the company signed – which turns into a 12.3 MW project pipeline.

The company is very light on total cash, and has $5.3 million in accounts receivable outstanding. The first number could be a challenge as labor costs make up a decent chunk of solar construction costs. Often times solar hardware can be obtained on pretty solid credit terms relative to payouts from customers as long as an executed contract is in place, and the project owner has finance lined up.

Regarding the accounts receivable, solar projects have a lot of milestone payments that can come along slowly as various aspects of projects are developed on long timelines. As well, very often projects are squeezed into construction timelines at the end of the year to secure the Investment Tax Credit benefits for the specific year. This happened quite a bit in 2019 since the tax credit fell from 30% to 26%.

As a C&I developer ourselves, who also has a contractors license, CommercialSolarGuy is a bit envious of a company like this. They’ve broken through the initial cash flow challenges and long term development cycles of medium-sized solar installations, and that is huge. Peck probably has a long future ahead of them, and I wish them the greatest luck in their endeavors.