The purpose of this post is to cover some of the on the ground work done, machines used, and one company’s techniques – Ernst Pollinator Service – when seeding a solar power plant to be local pollinator and sheep grazing friendly.

CommercialSolarGuy visited a solar power plant that was near completion located in south central Massachusetts. The facility was spread across multiple fields, totalling a few megawatts. While no project specific information was available, it is assumed this is a SMART contracted solar project, whose owners signed a twenty year power purchase agreement with the local electricity utility.

The inverters were manufactured by Chint Power Systems. The solar modules were a bifacial glass on glass product from LONGi Solar. Do please take a moment to note how clean and tight the wiring job is! Nice wire wraps for the large bundles, plenty of zip ties, and a generally well put together feel that feeds into the idea that other areas of the project were thoughtfully constructed.

With that, this article isn’t about solar hardware that generates electricity. This is about what’s going into the dirt below the panels – specifically the plants that will feed and attract the proper natural partners.

Roughly speaking, pollinator friendly ground cover costs starts at $2,500 per acre, which is about 1¢/Wdc in solar pricing terms. Adding a sheep grazing friendly seed mix to that ground cover increases the total by about $150/acre. It also happens to be that sheep grazing is a lower price than standard lawn mowers for land management.

While it simply makes good environmental sense to align a clean energy project with local fauna, it also makes financial sense in this project’s local market.

Within the SMART program, the State of Massachusetts has put in place a 0.25¢ (quarter of a cent) per kilowatt hour of solar electricity generated solar incentive. An average 250 kilowatts of solar panels, installed on one acre of Massachusetts land, will generates about 350,000 kilowatt hours a year – meaning the pollinator adder is worth $875 of revenue a year. Considering tax benefits on the up front costs, payback is under two years.

A link to the Pollinator-Friendly Certification Criteria for Massachusetts 2019/2020.

The seed is delivered by two machines – all terrain vehicle and a tractor.

The four wheeler has a seed distributor attached to the back that shoot the seeds under the solar panel racking. This is necessary at this particular site because the racking solution uses a lot of metal underneath the solar modules, and the large tractor can’t fit. This does affect how the seed takes to the dirt, as the tractor cut the ground, pushes the seed, and then squeezes the dirt. Throwing seeds mean they end up on top of the dirt.

Speaking with Lindsey White, you get clearly that she and her team are experienced land managers. To be honest, so much of the information rolls past myself as I try to keep up with Lindsey – and very specifically for the purpose of education of our company, CommercialSolarGuy brought along our Solar Design Engineer Benjie Borra (who is a Civil Engineer by training, with a State of Massachusetts General Contractor license).

For those who are into seeding, after a conversation about the types – and volumes – of crop used in various climate regions, and what it takes to create a long term, healthy meadow type environment – we got a great email from Lindsey re: cover crops recommendations:

Grain Oats: 30 lb per acre, planted January-August

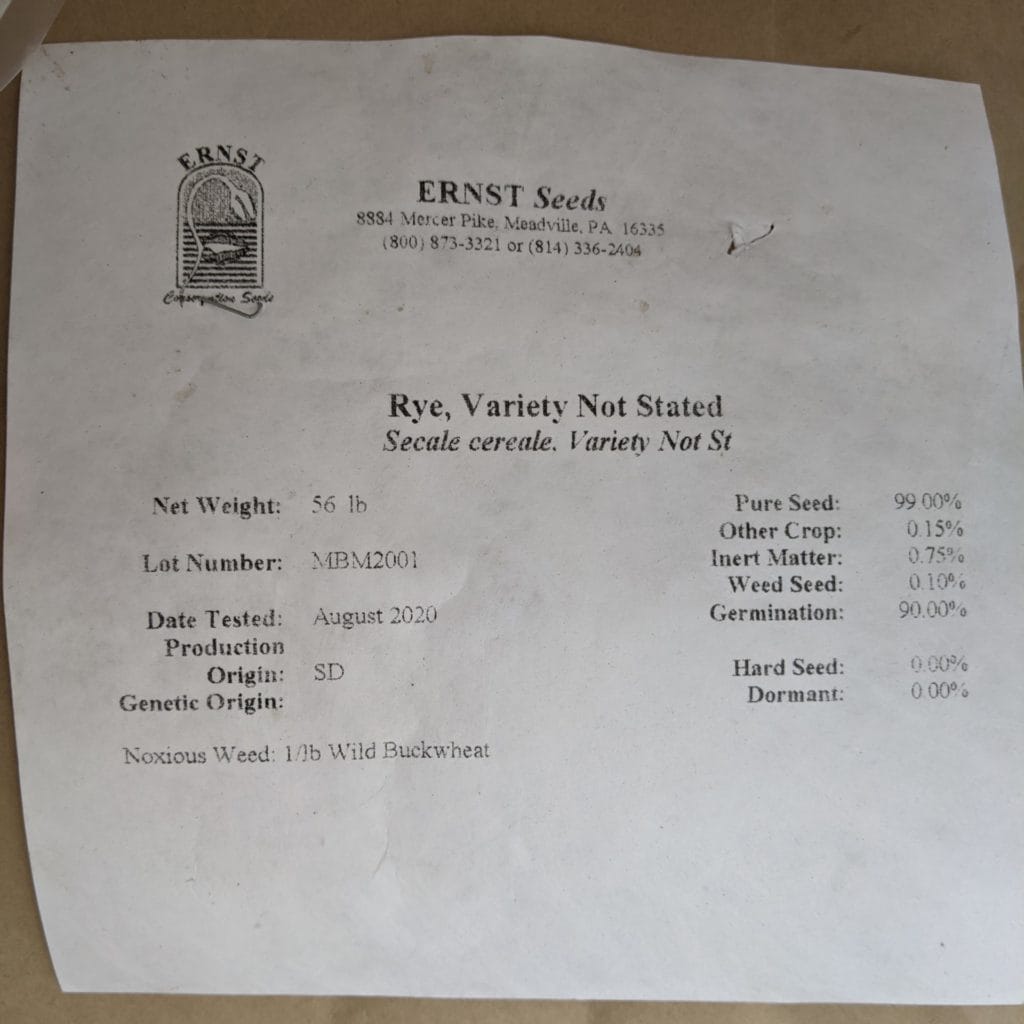

Grain Rye: 30 lb per acre, planted August-December (planted year-round on moist sites)

Brown Top Millet: 10 lb per acre, planted May-September (areas south of the Mason-Dixon Line)

Japanese Millet: 10 lb per acre, planted May-September (wet meadows)

These seeding rates are based on our experience with native meadows and our desire to establish strong, individual native plants. Planting cover crops that are too aggressive or thick diminishes the long-term viability of the perennial meadow plants. We have concluded that annual small grains, such as oats and rye, are the best cover crops or companion crops to plant with native seedlings when there is a need. Grain cover crops can reduce competition from aggressive weeds because they grow quickly and also reduce the potential for erosion by providing quick cover. We typically do not recommend annual ryegrass as it is too aggressive and can be persistent due to volunteer seedlings.

Two items that stand out, first – the volume of seed per acre is much lesser for this type of product than standards grasses. And second, Ernst has some deep and considerable land knowledge.

In speaking with land owners who are leasing their land to a solar power investor, there’s always a question on the handling of solar power hardware after the twenty year or longer lease agreements end. That answer is easy – we decommission the site. Roughly speaking, we know what it costs to remove the gear.

A real question though is – what’s going on in the dirt? What’s the quality of the soil going to be after this time? Companies like Silicon Ranch are thinking about this on a large scale level – even considering the carbon sequestration aspects of good land management.

Hearing Lindsey speak her vision on deep roots holding water, land being allowed to fallow, sheep doing their natural business – and I start again to get excited about solar power’s great land use responsibility.

Since I read about no-till farming, I asked if it applies in our industry:

A no-till drill seeder, equipped with a warm season/ fluffy seedbox is an invaluable tool when establishing native meadows. Can you plant a pollinator meadow with the use of such a tool? Absolutely! But the advantages are far greater when you consider better seed depth placement, better seed metering to keep seeding rates consistent, great seed to soil contact, and less soil disturbance to reduce soil erosion. Once existing vegetation has been killed, it takes a single pass with the tractor and drill seeder to impregnate that seed into the landscape properly. Alternatively, after killing the existing vegetation, you could plow the ground, roll it to ensure a firm seed bed, broadcast your seed, and apply straw mulch as a temporary soil cover. But that is four passes over the same area to get a finished product. It just makes sense, when and where possible, a no-till drill seeder, equipped with a warm season/ fluffy seedbox is a much better option.

I’ve said it before, with agrovoltaics (the combination of farming and ground mount solar power) turning into a real thing, as well pollinator and graze friendly facilities like these being built – it’ll come a time when solar is without a doubt a benefit to the land, in addition to the already existing financial benefits of land owners.